- Home

- Sharon Glassman

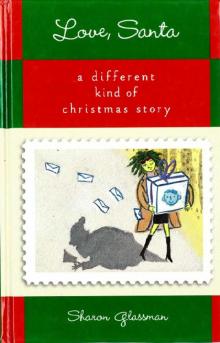

Love Santa

Love Santa Read online

Copyright

Copyright © 2002 by Sharon Glassman

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: November 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-57139-5

Contents

Copyright

Acknowledgments

Begin Reading

Epilogue

To the men and women of

Operation Santa Claus, and

Undercover Santas

everywhere.

Acknowledgments

A huge and heartfelt thank-you to everyone who so generously gave their time, assistance, and expert advice to this book, including Vincent Camastro, Pete Fontana, Pat McGovern, Andrew Sozzi, and Diane Todd of Operation Santa Claus; Undercover Santa party hosts Beverly Coyle, Angela Jobe, Sarah Martin and her team, Janet Pines and Bill Lukashok, Paul Ward, and Joey Xanders; my infinitely creative friends Frank DeCaro, Cori Nichols, Rosemarie Ryan, Scott Wadler, and Kris Waldherr; agent extraordinaire Dan Mandel; editorial goddesses Amy Einhorn and Sandra Bark; and my family, for showing that giving is the best gift of all.

December 22nd, 2 A.M.

New York City is lit up like one big Christmas tree. Yellow cabs race down its arteries between green and red lights. Champagne-fueled people in shiny, tight clothes weave in and out of late-night clubs like human tinsel.

But if you want to sample the biggest holiday celebration the city has to offer—the Real Christmas Deal—you have to come here, to the all-night main Manhattan post office on Thirty-third Street and Eighth Avenue, across the street from Madison Square Garden.

Within the post office’s humid, massive gray stone walls, hundreds of exhausted, frustrated—yes, even surly—citizens are only a few stamps away from true holiday satisfaction.

I know.

See that short Jewish woman with the curly red hair, the one with the alternating looks of agony and ecstasy flashing across her face? That’s me. I have been waiting in line here for two overheated, fluorescent-lit hours. But every minute I spend in line brings me one step closer to my first undeniably true experience of Christmas. And I’ve been waiting in that line for twenty twisted years.

I grew up ninety miles downtown in a suburban Philadelphia family that always got visits from Santa but could never (Oy, Gottenu!), ever, have a Christmas tree. Torn between assimilating or isolating us from Christmas, my not exactly religious but totally culturally Jewish parents made the Solomonic choice and did a little of both.

As a result, the holiday tableau in our house rarely jibed with the ones on traditional holiday cards. Although I bet there’s a thriving niche market for “bits of both” seasonal greetings in thousands of families along the CJNC—the Conservative Jewish Northeast Corridor.

Mixed-nuts imagery aside, my parents’ culturally kosher Christmas offered the best of both worlds in so many ways. And, as long as I was a kid, “the best” was fine with me.

But adults are born to raise trouble. More specifically, suburban Jewish adults are born to raise trouble for themselves. Growing up, I became mildly curious, then blatantly envious, and finally, totally, histrionically obsessed with test-driving that other kind of Christmas—the kind I watched television specials about with my family for all those years, and heard friends complain about in school.

Every January, on our first day back from the vacation that was nondenominationally rechristened “winter break” between fifth and sixth grade, my Christmas-celebrating friends would trade stories of disappointing presents, infuriating siblings, infinite church services, and undeserved holiday chores from the December 25 just past. Their voices echoed the world-weary tones our fathers now use to compare cholesterol counts.

But from where I sat, one cracked green lunch tray and yet a cultural world away, the events they took for granted were filled with magic and mystery. Unremarkable suburban dining rooms were transformed into operatic halls where ducks and hams were eaten midafternoon at tables laid with multiple columns of shiny flatware. Small- to medium-sized boxes tied with colored tinsel revealed geodes, penknives, and hand-blown bottles. Bigger boxes with telltale holes brought life-altering additions to the family unit or domicile: A puppy! A piano! No, wait—a synthesizer!

I listened to each story, almost speechless, eyes wide with envy, mouth full of school-issue fish sticks or homemade PB&J on rye. At my house, the arrival of a living animal or piece of nondesigner furniture would mean nothing less than a total breakdown in the social and aesthetic fabric of our lives, a personal invitation to anarchy, criminal behavior, or, the ultimate enemy, dust. For kids who did Noel, these changes were just what happened between each Thanksgiving and the New Year. Definitely better than their annual trip to the dentist, but infinitely more annoying than summer camp.

As a seminormal kid, I knew better than to admit how much I envied the holiday rituals my friends derided. Instead, I listened sympathetically to their Christmas war stories, shook my head, and randomly intoned our generation’s om, the singular word we used to honor an infinite range of emotional, physical, and experiential states: bum-mer.

But the invisible Hebrew letters in the imaginary cartoon bubble floating over my head spelled out the true story: “Bring on my first real Christmas, Rudolph,” they read from right to left in blazing emotional neon. “Bring it on!”

As college in Philly gave way to a supposedly more adult stage of life in New York City, I started to think of Christmas as this supercool A-list jock, cheerleader, and conceptual artist party that everybody on the planet was invited to except me: Ms. B-list, the cute but klutzy, semi-arty loser.

It all seemed so simple, yet so unfair. All I wanted was to partake of the holiday spirit everyone else shared so effortlessly—pine-scented, nutmeg-flavored, eggnog-drenched. To be as one with everything that was pure Noel on my own terms. I didn’t want to convert, but I didn’t want to feel like some cultural anthropologist reporting on another culture’s customs from the outside, either. Like a kid seized with holiday desire for a hot toy in a fake snow-frosted store window, all I wanted for Christmas every year was Christmas, damn it. All I wanted was a nice, bright, shiny Christmas that was MINE, MINE, MINE!

These are the noble motives that bring me here, to the main Manhattan post office during New York’s prime mugging hours, up to my bruised knees in packages for three kids I’ll never meet, kids whose letters to Santa I took home from this very building less than a week ago.

That’s when this trendy friend of mine clued me in about this thing called Operation Santa Claus, where otherwise-tough city people with holiday holes in their hearts can come down to the main post office and answer letters from kids who might not have a Christmas any other way.

A week ago, the world inside these august walls was terrifying terra incognita. Now I’m more familiar with its geography than I am with that of my apartment. I’ve stared at the walls for hours as I’ve waited in line. I’ve played that little game New Yorkers play when confronted with any unoccupied space larger than the hole in a pitted olive: What if I lived here? I’ve mentally covered the acres of postal marble floor with oversized sofas and love seats, put an imaginary industrial kitchen in the alcove by the northernmost door, and thrown a housewarming party for thousands of envious, invisible guests. But ultimately, I’ve decided that despite its architectural grandeur—or because of it—the post office isn’t the kind of place where I’d like to live, even in my dreams. I’m just your average, humble, two-bedroom condo kind of person. Or your average, humble, nineteenth-century triplex with a terrace, a garden, and an unobstructed view kind of per

son on a good hair day.

Depressed by the thought that I will probably never live in any of these spaces, I start looking for personally relevant messages in the government-issue slogans posted on the walls and over the doors. It’s a variation on the game I play with street signs in foreign countries, or the sayings in front of local churches. I don’t believe in fate, or divine omens, any more than I believe in affordable urban real estate. But I keep my eyes open, just in case some bit of eternal wisdom wants to connect with me in a down-to-earth but cosmic kind of way.

If you can believe the slogan on the banner hanging over the revolving doors: ’TIS THE SEASON TO GREET THE SPECIAL PEOPLE IN OUR LIVES. And the people in this lobby are very special indeed. The gray-haired woman on my right has just removed her dark blue loafers and hung them over her ears like two long and narrow leather muffs, possibly to filter out the scratchy choral rendition of “Silver Bells” playing on the postal PA system.

A few feet away, by the counter marked INSURED AND REGISTERED MAIL SUPPLIES, a subway conductor and bus driver in almost identical blue uniforms are voicing their heartfelt opinion that people with real jobs—that is, them—should be allowed—nay, required!—by law to cut in line. They pause for a second to see if anyone will let them cut ahead. Then they politely get in line with the rest of us.

It’s going to be a long night, ladies and gentlemen. Trust me.

To pass more time, I peruse the flyers from other government agencies posted on the wall between each postal window. They range from creepy-spooky to truly scary. The orangy-pink FDA flyer tells me to avoid this year’s most dangerous playthings, from electric bath toys to celebrity-chef dolls with tiny real knives. The malarial yellow ATF flyer asks all postal patrons to kindly leave our guns at home.

For the last half hour, I’ve been staring at the ceiling, where a different kind of message is spelled out in sculpted gold letters on the antique green tile panel over my head. The message, as I read it, says: DIEU ET SON DROIT. Which, if my high school French hasn’t expired, means “God and His right.”

If I were less delirious, I might stop to ask myself why God, if He exists, would choose to assert His rights in French on the ceiling of New York City’s only twenty-four-hour post office at two o’clock in the morning. And what is God doing here anyway? We’re here to mail letters, not chat with (possibly real) higher powers. But one thing I’ve learned these last few days of being an “undercover” Santa is that I’ll take all the help I can get.

At which point, God says in a French-Canadian accent just like that of the away teams’ announcers I’ve heard during hockey games at Madison Square Garden, across the street, “Please excuse my interruption, mais—but—what is this beautiful obsession you hold with Christmas?”

Can it be? Have I holiday-shopped myself into insanity?

“Allô, miss?” the voice says, from what sounds like the ceiling, thanks to the echo, but turns out to be from the guy standing right beside me in the bend of the line.

He’s got a beard—brown—and a smile—white—and two very nice-looking blue eyes. He’s got at his feet an official hockey stick and gym bag from the Canadian hockey team that beat the Rangers at Madison Square Garden earlier tonight. And a United States passport application in his hand.

“I have just finished my game,” he says. “Now I have come here to see about my application.” He’s really working the French accent thing. And it’s working. “And I see that you are—complètement—completely? Completely to the top with holiday spirit. All your boxes… your little bag of matching sweets. So nice!”

He points to the three-pound family-size holiday bag of Hershey’s chocolate Kisses in red and green foil that I’ve been fueling myself with for the last few days like a hiker with no compass but a lot of gorp. I offer him a chocolate.

It’s going to be a long night, but it’s suddenly gotten a lot more interesting.

“Man, you are really talking to the wrong person if you want to talk about the joys of Christmas,” I say. “I’ve got a tale of woe—do you know woe? Like misery? Pain? Right, pain! Well, I’ve got a tale of woe that’s longer than this line. And like so many things you’re not supposed to do in this country, the whole mess started with a big fat X.”

He smiles. A French-accented, irresistible smile.

“You really want to hear about Christmas?”

“Mais oui. But yes! That is why I have asked.”

“Okay,” I say. “But before we get started, I have to tell you that the passport office here doesn’t open until nine A.M. See that blue sign? The one that says passport window is open nine to five? You know, Neuf à cinq?”

“Thank you for showing it to me,” the man says, eyes flashing, beard doing whatever it is that beards do so devastatingly well. “Now I would like to hear about Christmas. Please.”

“Are you sure?” I ask.

“Bien sûr,” he says. “Of course. I believe, as you say, we both have all night.”

In the beginning there was Charlie Brown.

Every year from the time I was old enough to sit up until I was old enough to drive, from Thanksgiving through Christmas Eve, my ethnically Jewish, pop culturally pro-Noel family and I camped out on our red-and-green-plaid living room couch to watch a month of holiday television specials.

My mom went crazy for the shows in which sports team-size families of naturally straight-haired blond people sang perky and/or reverent songs around luscious fir trees laden with gifts and red bows. During the instrumental codas, she did these totally annoying fake ballet leaps in front of the set, until we screamed at her to please—okay, pretty-please—STOP!

From preschool until college, my sister’s and my number-one show, hands down, no contest, was A Charlie Brown Christmas. We were addicted to the swinging sound track and the redemptive message about the lovability of little trees, and little kids, as both of us were by far the shortest kids in our class.

But Charlie Brown and the tree were just the beginning, the appetizer, the hors d’ouevre. Our December TV Guide was the televisual equivalent of a bag of chips: Once we’d opened it and tasted that first special, we weren’t happy until we’d devoured every one.

(“Speaking of snacks, would you like another holiday foil-wrapped Hershey’s Kiss?” I ask Mr. Canada. “They’re from the suburbs of Philadelphia, just like me.” Did I really just say that? I can’t believe I just said that! But he just smiles and says, “You are very kind, thank you. Yes, please.” )

Every year, we booed the Grinch’s selfishness and applauded his ever-expanding heart. We gave Rudolph extra credit for saying no to that nose job while triumphing in his chosen field, like one of our other major cultural idols, Barbra Streisand. We even watched The Year Without a Santa Claus, the special whose creepy villain, Heat Miser, combined with its weird style of animation, gave me recurring nightmares of being chased through an annoyingly repetitive landscape by arthritic monsters.

But every year, Frosty melted Heat Miser’s heart. And every year, after two weeks of watching the singing and the snow and the never-ending stories of redemption and happiness, my family melted into a comfort and joy-infused teamlet of four height-challenged brunettes who, for a few heedless days, were as naturally, as blondly committed to the spirit of Christmas as the Williamses, the Crosbys, and platinum white Frosty himself.

One mid-December day after school, when I was ten years old and my sister five, I took her to the park around the corner to see if we could talk a lonely little tree into becoming insanely lush and beautiful, like the one on the Charlie Brown special. When that plan failed, we built a snowman, which we decided could come to life only when no one was looking. It was my first experience with the power of a creative backup plan.

That Saturday, my dad drove us across our suburb to see the Palermo family’s house, a white stucco two-story that was miraculously re-created every December with thousands of dollars’ worth of illuminated sleighs and reindeers and red, green, and wh

ite lights. Everybody in our corner of the greater Philadelphia area visited the Palermo house during the holiday season. It was as de rigueur as watching the feather-clad, ukulele-strumming Mummers strut through Center City on New Year’s Day.

On Saturday nights, Mr. and Mrs. Palermo got dressed up as Mr. and Mrs. Claus in matching sets of his and hers white wigs, red suits, and Brooks Brothers penny loafers. As the kids lined up to talk to Santa, the adults thanked Mrs. P. for another unforgettable display and the little cup of “corrected” cocoa she offered from a silver platter. Despite our differences, all of us children—sporty and nerdy, tall and small—asked Santa for the same blessed thing at the end of our Christmas list: to make our parents as rich as Mr. Palermo, so we could have amazing lights at home next year, too.

Driving home, my mother, spirits spiked with Palermo cocoa au rhum, invented a new form of Christmas torture: an original medley of her favorite Christmas carol titles, which she sang over and over again to the tune of “Jingle Bells” and ended with a calypso beat.

“Jin-gle BELLS! Sil-ent NIGHT! WE THREE Kings are—Everybody now!” My sister and I pretended to have died from shame in the backseat. Three verses later, when my mother still hadn’t stopped singing, we started snoring to show her that while we were not technically dead, we were dead asleep and deserving of silence.

Two blocks later, a sonic Christmas war was raging in my dad’s blue-on-blue Buick. The louder my mother sang in the front seat, the louder we snored in back. Then we added snorts and whistles, which were never as convincing as we wanted them to be, because we couldn’t stop laughing. Which totally pissed us off. We didn’t mean to laugh! Which was the thing that finally pulled my dad into the game.

“Does anybody hear any snoring back there?” he asked, looking into his rearview mirror and making this blatantly fake “I’m so confused” face, which made us laugh even more. By the time we pulled in the driveway, everybody was crying and hiccuping, laughing so hard that my mom promised to sing even louder next year.

Love Santa

Love Santa